It goes without saying that 9/11 has been the most significant event of the last 25 years.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, no single day has so radically altered how we - that is to say, the English-speaking world and the West - see our society, our governments and our structures.

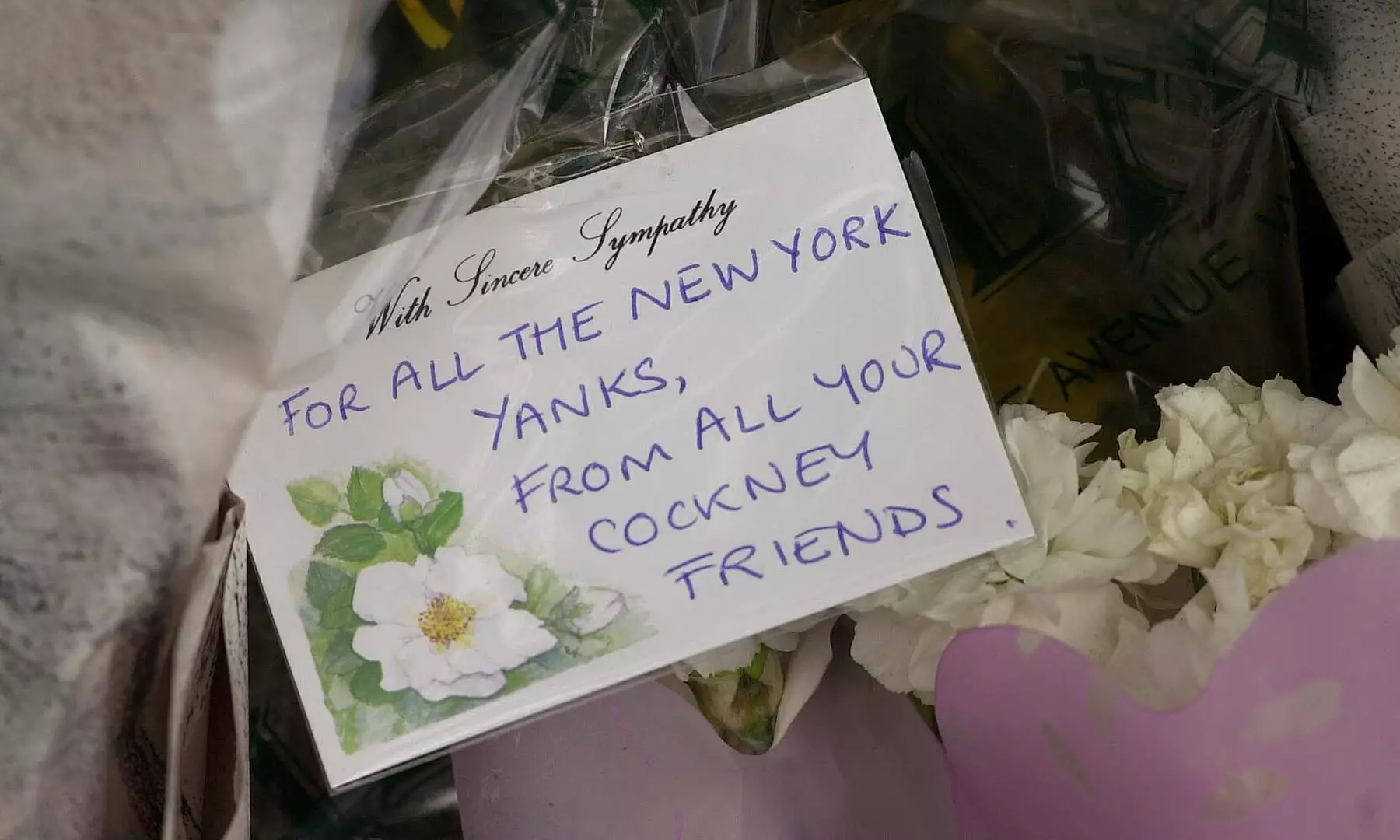

The success, for want of a better word, of the terrorists who attacked the United States on September 11 2001 has been to make people - not just New Yorkers, not just Americans, but all those who saw war as something that happened to other people in a far off, distant place on the evening news - fear each other.

Before the September 11th attacks there was terrorism and war in the world, but we didn't think it could reach us. 9/11 proved that it could.

Credit: PA

Terrorism, by definition, is designed to spread terror. The death toll and physical destruction is secondary to the ripple effect that the act has on the consciousness of those who witness it, whether in person or on television or after the fact.

Bearing this in mind, we should discuss the fears and perceptions of Westerners before 9/11 and assess where our priorities lay, so that we can see how they changed.

On September 10 2001, Donald Rumsfeld, the US Secretary of Defense, gave a speech at the Pentagon that described 'bureaucracy' as the biggest threat to America and proposed massively slashing the intelligence services' budget.

It was not that terrorism did not exist: in 2001 alone, there had been IRA bombings in the UK, countless bombings in Colombia, insurgencies in the Balkans, in Chechnya and Sri Lanka, ongoing internecine conflicts in Angola, Somalia and the Congo as well as the Second Intifada in Palestine, which was a year old.

It was just that we thought that they were something that happened miles away. You didn't know who Osama bin Laden was, despite him having been the most wanted man in the world since 1999.

Credit: PA

9/11 made terrorism something that happened elsewhere into something that could happen here and thus people were afraid of it. The evidence doesn't back up the fear - Americans, for example, are far more likely to be killed by a toddler than by a terrorist, while guns cause the equivalent deaths of a 9/11 every three months - but fear is not something that can be quantified by evidence. Fear is irrational.

Terrorism works because you are afraid of it and you are afraid of it because it is scary. When the response to 9/11 was to massively heighten security, it reinforced the idea that terrorism was a thing that could happen and reminded you that it had happened.

Every time you get on a plane, the security reminds you of 9/11. Before the attacks, there was no TSA and no such thing as the Department of Homeland Security.

The national conversation in America had been defined, since the fall of the Soviet Union, by how the state was too big. Now, the defence budget has ballooned beyond measure.

When the War on Terror was announced on September 16, George Bush was using a rhetoric to which Americans were accustomed. Lyndon Johnson had a war on poverty, Richard Nixon had a war on drugs, but this time that war would be fought with an actual army. Fighting an actual war against an abstract concept is, of course, impossible, so a placeholder was needed to fill in, and that was to be Al Qaeda.

Suffice to say, before 9/11 very few people knew what Al Qaeda was and even fewer were afraid of it. Because of this, the vague notion of Islamic terrorism was taken as the enemy, with many feeling that the Islamic part was more important than the terrorist part.

While previously the terms Muslim American was no more relevant than Christian American or Hindu American, now the entire Islamic community was to be held accountable for the actions of people they hadn't heard of either. Islamophobia grew massively and individual Muslims suffered hugely.

Credit: PA

A war against Al Qaeda, a group with no physical base and no concrete structure, was only slightly more possible than a war on a concept, so the target of the war would be the Taliban. The Taliban had been in power in Afghanistan since 1996 and, though none of the hijackers were Afghans (15 of the 19 were Saudis, as was bin Laden), it would be Afghans to bore the weight of the international backlash. The Iraqis would follow, of course. The effect on the political map of the Middle East after 9/11 cannot be underestimated.

In 2001, the dictators of Iraq, Syria, Tunisia and Egypt had been in sole power for decades, heavily backed by the United States in the name of regional stability.

Now, all except Assad in Syria have been toppled by their own people, with the civil war in Syria still raging. It is hard to see how the Arab Spring could have happened without the huge destabilisation caused by the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Before 9/11 forced their hand, the American establishment had a great deal: the dictatorships ensured stability and stability allowed oil, and oil revenues, to flow, while nobody back home asked too many questions about what those regimes were doing.

Once international terrorism shone a light on some of the murkier corners of the Middle East, it became untenable to allow them to go back into the shadows.

When the Americans used democracy as a reason to invade Iraq - they opened a box that could not be closed. One could not depose Saddam for democracy's sake and resist the same claims from the streets of Egypt, Tunisia and Syria against their tyrants.

America sets the international agenda, and before 9/11, terrorism wasn't on it. At July 2001 G8 Summit in Genoa, leaders discussed poverty reduction, the environment, debt forgiveness and globalisation.

Now, international cooperation is defined by the war on terrorism and will continue to be for the foreseeable future. 9/11 fundamentally changed our relationship with fear and the orientation of our international agenda.

Credit: PA

For the 11 years between the end of the Cold War and the start of the War on Terror, there was a threat deficit: America stood, unopposed, as the only superpower. Now, there is a threat, but no way of combatting it. Where once there was the Soviet Union, today we face an idea.

The filmmaker Adam Curtis calls the condition 'Oh Dearism': the constant cycle of terrible events to which one can only say: "Oh Dear", whether terrorist attacks, natural disasters, economic events or ongoing, intangible threats.

One could take solace, at least, that 16 years on from 9/11, we might have a new, real, physical threat that inhabits a place and can be attacked - if that makes anyone feel better.

Advert

Words: Michael Wood

Topics: terrorism, 9/11, New York, terror attack