It is a year ago today since Manchester was hit by one of the most devastating terror attacks ever carried out in Britain.

Twenty-two innocent people were killed and many more were injured when a suicide bomber detonated a device at the city's arena during an Ariana Grande concert. Many of the victims were children.

Yet if ISIS suicide bomber Salman Abedi - a 22-year-old born in Manchester - hoped his act of hate would sow only fear and division, he failed miserably.

In the hours, days, weeks and months following the atrocity, stories of courage, hope, love and the indomitable human spirit could be found everywhere.

To pay tribute to those who tragically lost their lives, we hear the devastating stories of people who were there.

THE SURVIVOR

Advert

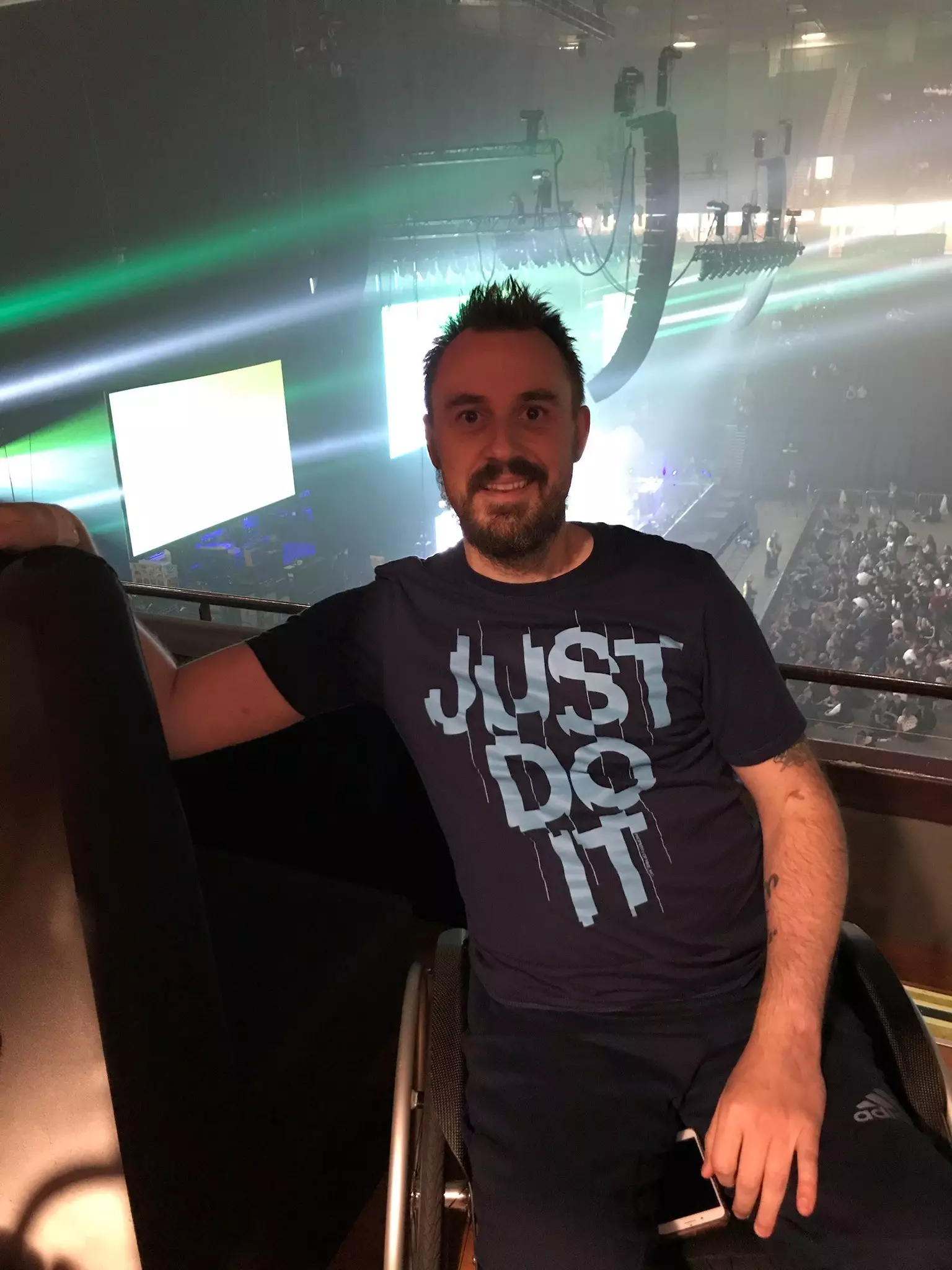

Martin Hibbert was stood closer to the bomber than almost anyone else who survived.

The football agent, from Bolton, was at the concert with his 15-year-old daughter. Doctors said his injuries were similar to being machined gunned with 22 bullets at point-blank range.

"Ariana Grande had been brilliant. We'd loved every moment of the show but she was over-running and I wanted to beat traffic, so we decided to leave during the encore.

Strange how the smallest decisions can have the biggest consequences. Heading out early meant we were in the foyer just as the bomber detonated himself.

I bumped into him, actually. The police told me afterwards. Apparently as I rushed through some doors, you see us on CCTV coming together. A shame I didn't chin him, isn't it? A few moments later the explosion happened.

It's hard to describe. The world just shook and boomed, and then there were screams, and you were no longer at a concert; you were in hell, really, a horror movie.

I was on the floor and couldn't move. Twenty-two pieces of shrapnel had shot into me. My body was full of golf-ball sized holes. There wasn't a part of me that wasn't bleeding. I saw a leg lying close by and I remember wondering if it was mine and making an effort to look down. It wasn't.

My daughter was lying about five feet away, unconscious. Her head had been shot open by the shrapnel. I couldn't move to her and could barely breathe but I was trying to tell her, 'hold on, kid'. I don't know if she heard.

I'd seen on a film that the best thing to stop a wound bleeding is hold a credit card over it and I tried to reach for my wallet but, after five minutes, I realised it wasn't even there anyway. So, I just lay, trying to stay conscious. I was more tired than I've ever been in my life. I made a pledge with myself - I'd stay awake until they got my daughter out and, after that...we'd see.

I was there maybe 45 minutes. At some point someone put a sheet over her. I was growling to get their attention. I was telling him she's still breathing and they looked at her again and then they were carrying her out on a stretcher, and I was so thankful. I was thinking, 'that's your job done'. I'd made peace with the fact I was dying.

I was unconscious when they got me to Salford Royal Hospital.

I had two seven-hour operations to remove the nuts and bolts. My feet, legs, arms and jaw were all smashed. One had severed my spinal column. My throat had a part missing. There was one bolt in my face they couldn't get but it eventually rose to the surface and broke the skin itself. I tweezered it out. I keep it in a jar.

The bolt that severed my spine means, doctors say, I may never walk again. Maybe they're right but I've managed to move my toes which I was told would be impossible so I refuse to give in. I keep doing my exercises, keep seeking treatment, keep trying to push things forward.

My daughter has been left brain-damaged and in a wheelchair but she has the same spirit as me. She can't speak but she can see and hear, and she writes things down. It's devastating but I remind myself that, lying on that arena floor, I'd have done anything for her just to be alive. In that moment, I'd have taken this.

As a family, we're refusing to let terrorism win. I'm back working a little and trying to live as regular a life as possible. I'm doing the Manchester 10km on May 20 to raise money for three hospitals. If I can complete that it feels like a huge two fingers to the terrorists."

THE POLICE OFFICER

PC Jason Hague, of the British Transport Police, was on duty at Sheffield train station when he first heard of an unfolding but unspecified incident at Manchester's Victoria station, which is linked to the arena.

As the 31-year-old, from Sheffield, sped to the scene, the sheer scale of the atrocity started to emerge over the radio. When he arrived, the injured were already laid on the concourse at Victoria.

"Whenever I think back to that night, my overwhelming memory is of the colour red.

Blood was everywhere. In puddles on the floor, all over the walls, drenching the injured. There was literally a red tint in the air. I've dealt with some horrific fatalities working on the railways but nothing I've ever seen came close to the concourse of Victoria Station that night. I struggled to sleep for a while afterwards.

We'd received a call just before I was due to finish my shift. It said there was a fatality and assistance might be needed. Sheffield is 40 minutes away so my colleague, PC Richard Ward, and I started driving over.

I think, at first, we thought we'd probably be turned around half way there but I remember a message coming over that there were actually three fatalities and suddenly we were fearing the worst. Then the count went up again. We were in the car listening to it unfolding on the radio, feeling helpless, trying to go faster. It was the longest journey of my life.

By the time we arrived, there were 19 dead. We knew it was a terror attack. Ambulances were parallel parked everywhere. I remember walking into Victoria and just seeing a mass of injured people - open wounds, missing limbs, agony everywhere you looked, young and old, children. There were bodies covered over.

I think the only way you can process something like that is to go on automatic and start helping. I opened my first aid bag and threw bandages to people, provided a doctor with some equipment, then got to work treating the more severely injured. I don't remember who or how many. The only one that sticks in mind was a little girl. She was unconscious; hips, ankles and jaw all broken, fingers shredded. Her shinbones were sticking out. I did what I could, and when an ambulance came for her, she was still alive. Amid the devastation, that felt like a victory.

I was there four hours in all. The bravery on the survivors was inspiring. They had battle field injuries but they kept calm. The courage on show that night was astonishing. Someone asked later if I was worried another terrorist might be on the loose but you don't think about it. You trust your armed colleagues to deal with that. It was my job to help people.

It's probably obvious to say but you can't see things like that and not be affected by it - even if you've had all the training in the world. But I have no regrets I was on duty that night. My entire professional life has been about helping people and keeping them safe. I would be at a similar incident again in an instant. All my colleagues would. In the end it's pretty simple: terrorism won't win."

THE SURGEON

Dr Peter-Marc Fortune is a paediatric surgeon in the intensive care unit at Royal Manchester Children's Hospital.

The 55-year-old, who lives in the area, became aware of the attack when a chat group used by the centre's consultants started vibrating with messages. He would spend the next two weeks carrying out operations on survivors.

"The injuries I dealt with that week weren't anything I was ever expecting to see without doing voluntary service in some overseas unrested area. It was comparable to serving in a warzone. They were war injuries.

As a surgeon, you deal with life and death situations on a weekly basis. I have seen some horrendous road traffic accidents down the years. I don't pretend you get used to it but it's the job - we're fortunate to be able to save lives. But there was a horror associated with this, with the volume of casualties, the nature of the injuries, the whole thing of that sat behind it - terrorism at a concert - that was haunting.

I found out about the attack on my phone that night. The intensive care unit has a closed discussion group for surgeons, and there were messages on there. My initial instinct was to go in to the hospital but I was told the unit was coping and I should get some sleep to be fresh the next morning. I didn't get much.

I have never seen intensive care so busy as it was that Tuesday. The main things we were dealing with were shrapnel injuries, nuts and bolts which had embedded in people or which had passed right through. But what was striking was the sense of calm. The whole team was there - expert doctors, nurses and auxiliary staff - and they swung into action exactly as you would want: calm, professional, quick. Everything worked. We have never looked back and thought we could have done things better. The unit did a brilliant job.

The strangest thing for me was the first patient who came in. They hadn't been identified so they were just a number. I've never worked on someone like that. Even in the most serious road collisions you normally know something about who you're treating. But during a break, one of the nurses recognised this person on social media and told the police, and so the family could be told their loved one was alive. Just thinking about their relief - that was a good moment.

I got a bee tattoo afterwards. Lots of people were doing it. I was chatting to some colleagues and I said I might get a T-shirt and they said, 'oh come on, you can do better than that'. So, I said, if I could raise a suitable amount I'd do it. And £5,000 later I had a tattoo. It's a tribute to Manchester's spirit."

THE CITY LEADER

Andy Burnham, a former secretary of state, is the elected Mayor of Greater Manchester. He had been in post just two weeks when the attack happened.

The 48-year-old has been widely praised for his leadership of the city in the days and weeks that followed.

"The night itself, as soon as I started receiving calls, was a moment that will live with me forever.

The following day I was in the city centre from around 4am. I remember Manchester feeling jittery, a very strange atmosphere which, I think, we all felt.

As the day wore on we discussed whether or not we should hold a vigil and, in the end, it was decided we should. Looking back, I realise it was the single best thing we did because bringing the city together allowed people to find comfort from each other and for the character of the place to reassert itself. It allowed Manchester to find its voice again and begin to face its future.

There were mixed emotions of course. People were numb. Everybody was trying to make sense of what had happened and, at least immediately, it proved impossible to do that given the enormity of the situation. But there was a sense of togetherness in Manchester, of people going above and beyond for each other.

That only grew in the days and weeks that followed, and I remember how exceptional a time it was in terms of how people pulled together.

A year on, it is important to say that the pain is real, as is the hurt and the anger. That will never go - how could anyone target those people in that way?

But in the end, you realise it does not help to dwell on those feelings. The only way to defeat terrorism is to show defiantly that the vast majority of people won't be divided. That is the best counter to the rising extremism we see around us.

I like to think in that moment, in May 2017, Manchester was a beacon of hope for the rest of the world. It is possible to be sorely tested but to not let violence win."

Interviews and words: Colin Drury

Topics: Inspirational, Ariana Grande, Manchester, UK, Inspirational, Ariana Grande, Manchester, UK