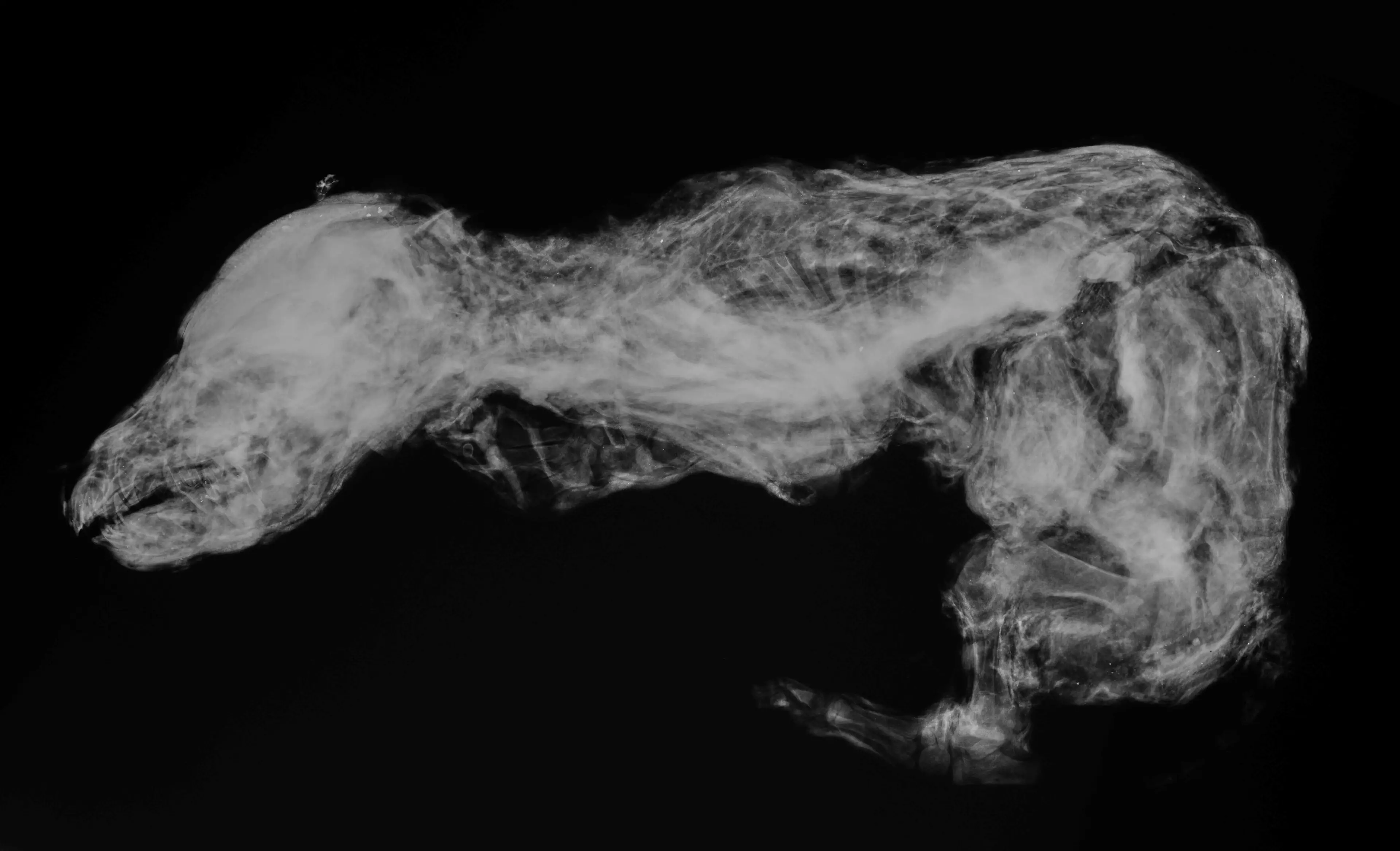

A mummified wolf that was buried under the snow in northern Canada 57,000 years ago has been unearthed, and it is remarkably well preserved.

It's been so well kept by the freezing temperatures underground that it still has fur, teeth and skin intact, making it a completely unique find.

The remains were dug up by a gold miner near to Dawson City in the Yukon region, and it throws wide open a window on the prehistoric world that the wolf cub would have lived in.

For a short while, at least.

The female cub was just seven weeks old when the den it was being raised in collapsed around it. Experts believe that to be the most likely cause of death.

The discovery tells a story of a world when woolly mammoths roamed the earth and - because of how well the wolf's body has survived - it helps us build up a picture of the evolution of wolves throughout the thousands of years.

This specimen is the oldest wolf on record, and the scientists who get chance to study it are quite rightly very excited about the prospect.

Julie Meachen, a professor of anatomy at Des Moines University, said: "She's the most complete wolf mummy that's ever been found.

"She's basically 100 percent intact - all that's missing are her eyes.

"The fact she's so complete allowed us to do so many lines of inquiry on her to basically reconstruct her life."

The animal has been given the name Zhur, meaning 'wolf' in the Han language, local to where it was found.

The find is rare, particularly because it remained entombed in the permafrost for so long.

Professor Meachen explained: "It's rare to find these mummies in the Yukon.

"The animal has to die in a permafrost location, where the ground is frozen all the time, and they have to get buried very quickly, like any other fossilisation process.

"If it lays out on the frozen tundra too long, it'll decompose or get eaten."

"We think she was in her den and died instantaneously by den collapse.

"Our data showed she didn't starve and was about seven weeks old, so we feel a bit better knowing the poor little girl didn't suffer for too long."

Meachen's colleague Professor Matthew Wooler, from the University of Alaska, added: "For scientists, this is a different kind of gold."

Zhur is now on display at the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Whitehorse, Canada.

Featured Image Credit: SWNSTopics: Science, Interesting, History, Animals, Canada