Maria Gonzalez is prominent in the documentary. She depicts the countryside daubed with dead farmers. Credit: Michael Gillard

Award-winning journalist Michael Gillard writes about the importance of chocolate for lasting peace in Bogota, Colombia.

A chocolate producing community of peasant farmers who were massacred after declaring themselves neutral in Colombia's five-decades-long civil war could hold the key to a lasting peace as a ceasefire began recently.

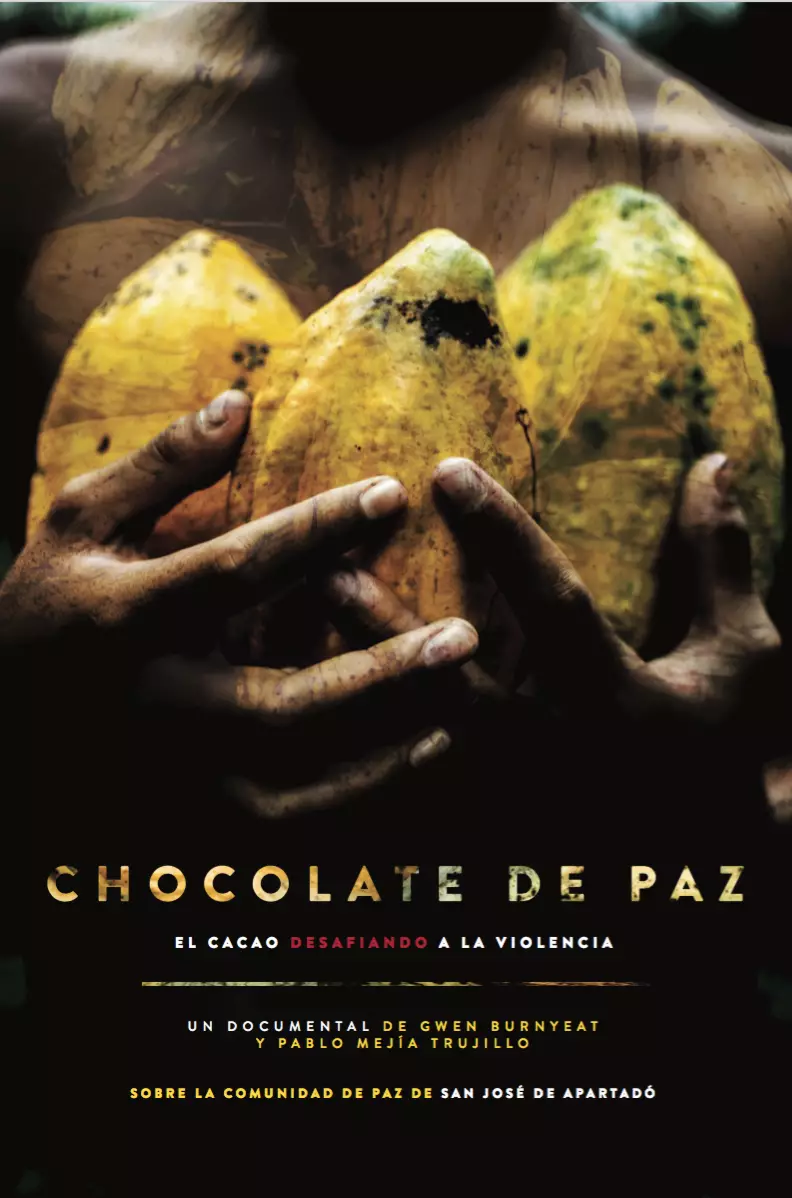

The San José de Apartadó peace community is the subject of a timely documentary by British anthropologist Gwen Burnyeat.

The documentary gives an insight into decades-old conflicts between farmers, Farc rebels and the government.

Advert

Timely because Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and Marxist guerrilla leaders of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) will sign a historic peace deal this month after four years of talks in Cuba.

Since it was established in 1997, at least one quarter of the 1200-strong San José peace community have been assassinated, mostly by government-backed paramilitary death squads.

Burnyeat, who spent two years living among the cacao farmers, says Chocolate for Peace, her documentary, was inspired by the community's ability to sustain a co-operative spirit amid such chilling political violence.

"Signing a peace deal is one thing, but Colombians are wondering how peace will happen post-conflict. The San José community has been doing that for 19 years since they declared themselves neutral. Their experience will be essential considering that change is going to take generations to achieve," she explained after a showing of the documentary to well-heeled university students in the capital Bogota.

Gwen Burnyeat. Credit: Michael Gillard

Advert

Mauricio Rodriguez, the former Colombian ambassador to the UK and a close ally of President Santos, agrees. "Peace," he said, "is much more than signing an agreement. It is a daily task for many years for all citizens and the state rebuilding trust, healing wounds [and] strengthening institutions, especially in remote areas mostly affected by the conflict."

The community in the northwest region of Uraba has had more recognition abroad for choosing neutrality over flight than at home among war fatigued Colombians, says Burnyeat. Every Saturday, she helps run a "peace breakfast" where Bogotanos listen to the experience of San José farmers over a hot chocolate. President Santos has promised to attend.

Kirsty Brimelow QC, chairwoman of the Bar Human Rights Committee, who has just returned from visiting the community, found them in a cautious mood.

The barrister mediated for the community when, in 2005, the army and paramilitaries massacred eight people, including their outspoken leader and three children, among them Santiago Tuberquia, an 18-month-old boy.

Then president, Alvaro Uribe, justified the massacre by labelling the San José community as guerrillas. Today he is a key far right wing opponent of peace talks with the Farc.

However, two years ago, Brimelow secured an apology from President Santos, the former defence minister in the Uribe administration, who now praises the community's good work.

"The president said forgiveness must be a condition of peace and I agree, in the same way that an apology by the state can go some way to healing the suffering that Colombians have endured," she said.

The often dirty war between guerrilla groups and government forces and their paramilitaries allies has claimed over 220,000 mostly civilian lives and displaced six million more since peasant farmers first took up arms over land inequality in the mid-1960s.

Brimelow recognises it is hard for the San José community to forgive. However, he says: "While impunity must not prevail and historical memory is hugely important, so too is the necessity for a change from a victim's narrative to a narrative of reconciliation and hope for future generations."

Chocolate for Peace aims to do just that, says Burnyeat, who made the film with a £3000 donation from a friend of her mother, the poet, Ruth Padel, a great, great grand-daughter of Charles Darwin.

The 30-year-old lecturer has spent much of her six years in Colombia defending herself against claims of being 'a little gringa romanticising the peace process'.

But a two-year spell in San José de Apartadó working for the Peace Brigades has ensured that Burnyeat's interviewees go beyond "the usual human rights patter" and are insightful about their relationship with the land they refuse to abandon and the importance of their co-operative approach to processing their harvest for sale.

Lush, the UK cosmetic chain, already buys 100 tons of certified organic cacao beans from the community every year and supports the Peace Brigades' presence in San José.

Maria Gonzalez, a star of the film, produces paintings depicting a rural "paradise" blighted by the corpses of macheted farmers. "When the Black Hand paramilitaries came, happiness ended," she recalls. "We want to build a dignified life and seek justice not revenge."

When the Farc last entered into peace talks in 1985, a grassroots leftist political party, the Patriotic Union, emerged. But within a decade, death squads working with politicians, landowners and the army had assassinated two presidential candidates and 5000 members, including leaders of San José de Apartadó farmers' co-operative.

Jesus Emilio refused to admit to being a guerrilla when the paramilitaries tortured him. "I am unashamed to call myself a campesino (peasant farmer). My grandparents were campesinos. I have dirt for blood," he says proudly.

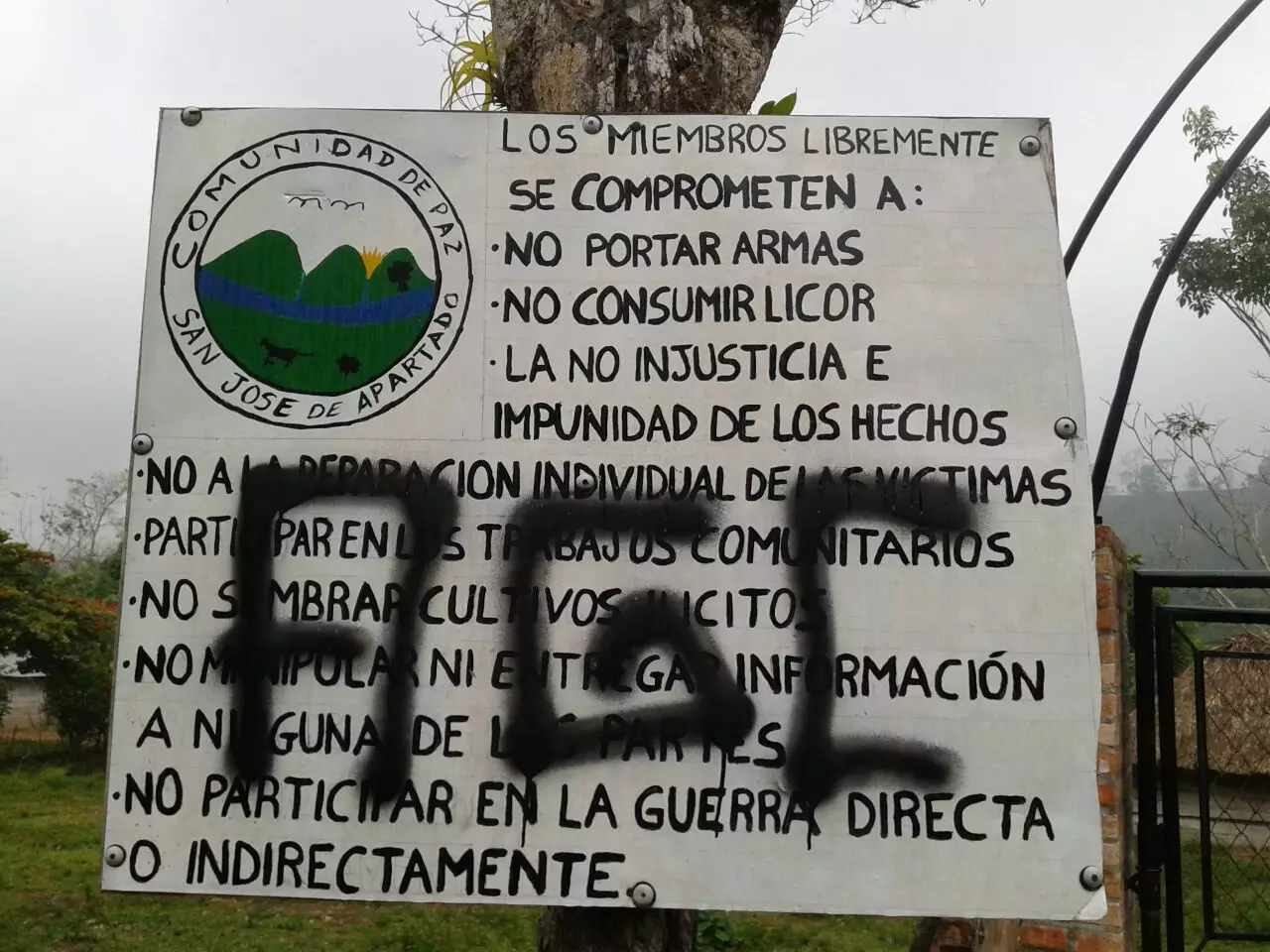

There may be talk of peace in Havana, Cuba, but the San José community remains under threat. A paramilitary group recently daubed their walls with graffiti, warning: "We are coming to finish you off".

This is not just typical graffiti. It's a chilling threat. Images Michael Gillard

President Santos, who is said to be eyeing up a Nobel peace prize if he can pull off a deal with guerrilla groups, claims the paramilitaries have been dismantled and what remain are criminal groups.

His ally, Mauricio Rodriguez, said: "The government has been successfully fighting all illegal and violent groups. One of the points of the peace agreement deals with post-conflict security and retired General Naranjo - one of the most admired officers in Colombia's history - is responsible for the design of these plans, especially in the most affected regions."

But Peter Drury, who monitored Colombia over 20 years for Amnesty International, says the paramilitary presence in a region like San Jose where the army is strong points to "continued close collusion" and "a lack of political will" to truly dismantle them. "The question is," he adds, "who is defining peace and for whom? The international community must be alive to the danger that any peace process does not just serve to guarantee the impunity of serious perpetrators of human rights abuses."

Come what may, Jesus Emilio is staying in San José. "Despite those who want me dead, I can't leave," he said. "I'd prefer a grave here than asylum in Europe in a luxury apartment."

Words Michael Gillard

Featured Image Credit: