Researchers in the US have discovered a 'new' organ in the human body which may cast some light on how tumours spread, raising hopes that in the future it will be possible to detect them earlier on.

Known as the interstitium - a shock-absorbing tissue underneath the skin, gut and blood vessels - the discovery was previously thought to be connective tissue, but has now been identified as an organ for the first time.

The discovery was initially made by mistake, as is often the way with major scientific discoveries (such as Penicillin).

Advert

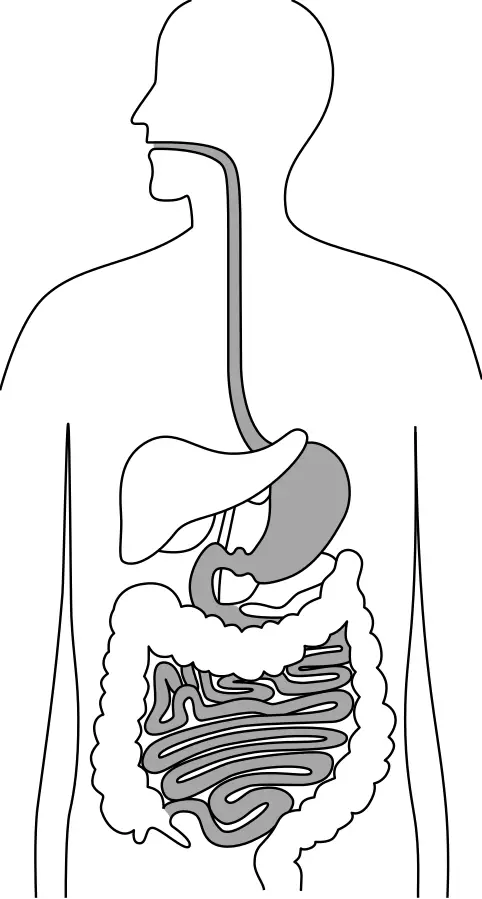

As reported in New Scientist, a team of researchers were carrying out routine endoscopies - procedures which involve inserting a thin camera into a person's gastrointestinal tract, which goes from the mouth to the anus.

The procedure lets doctors inspect human tissue. As New Science reports, one of the teams carrying out an endoscopy had expected to find that 'the bile duct is surrounded by a hard, dense wall of tissue'.

However, what they instead discovered were unusual patterns, which they then took to Neil Theise, a pathologist at New York University School of Medicine.

Advert

Theise carried out the same procedure on himself, inspecting the skin under his own nose, and discovered similar results, which suggested the patterns are made up of fluid found throughout the body.

The pathologist now believes that each tissue in the body might be surrounded by a network of channels which essentially make up an organ containing a fifth of a human's total body fluid.

"We think they act as shock absorbers," he said.

Advert

Past technology meant that the appearance of these networks of fluid would not have shown on scans, and Theise and his team now believe that the discovery may be useful in cancer detection. They looked at samples from people with invasive cancers and noticed that tumours were spreading in a similar way.

"Once they get in, it's like they're on a water slide," he told New Scientist. "We have a new window on the mechanism of tumour spread."

Essentially, it's believed that the interstitium is helping cancerous cells travel directly to the lymphatic system, which carries lymph fluid directly to the heart and is a key part of our circulatory system.

Advert

Theise and his team are now conducting further analysis on this newly discovered fluid to see how it might aid physicians in detecting (and therefore treating) cancers earlier on. The team also believes the fluid might also be linked to oedema, a rare liver disease, and other disorders.

Theise is a diagnostic liver pathologist and adult stem cell researcher, as well as Professor of Pathology and of Medicine at Beth Israel Medical Center of Albert Einsten College of Medicine.

Featured Image Credit: PATopics: Science, World News, Research, USA