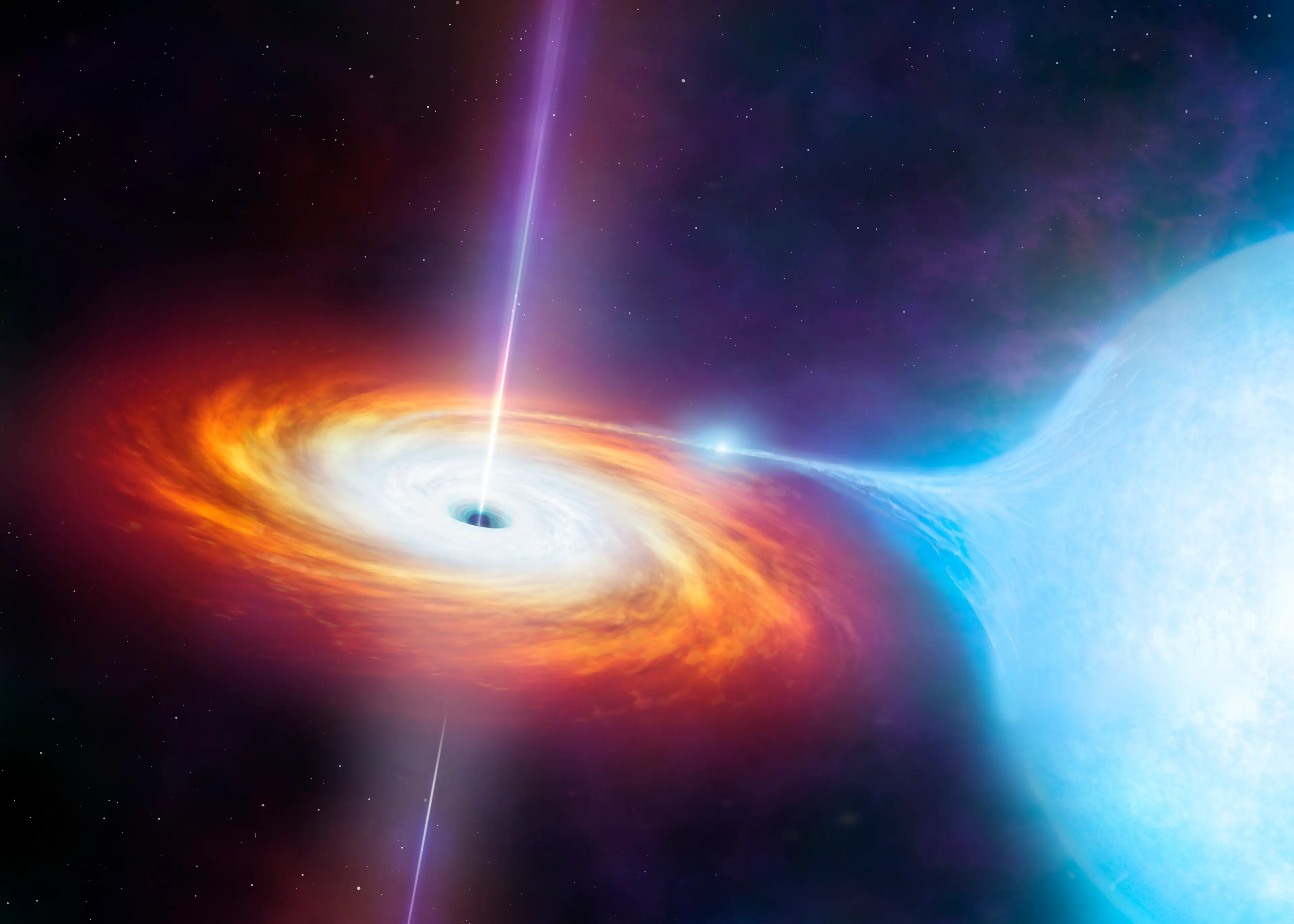

Some of the world's leading scientists have proven one of Albert Einstein's theories about black holes to be absolute correct.

The finding comes more than 100 years after the legendary theoretical physicist made the bold prediction, made way back in the First World War.

It comes just days after NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, made by the space agency at a cost of $10 billion, made a groundbreaking discovery about black holes after it captured them smashing in to each other for the very first time in history.

Advert

The space agency has also in recent weeks released a full simulation of what it would be like to fall through a black hole and pass its event horizon.

With Einstein's prediction, made back in 1915, it has been proven true thanks to the work of an international team led by researchers at Oxford University Physics.

The team at the university has been using X-ray data to test Einstein’s theory of gravity and black holes.

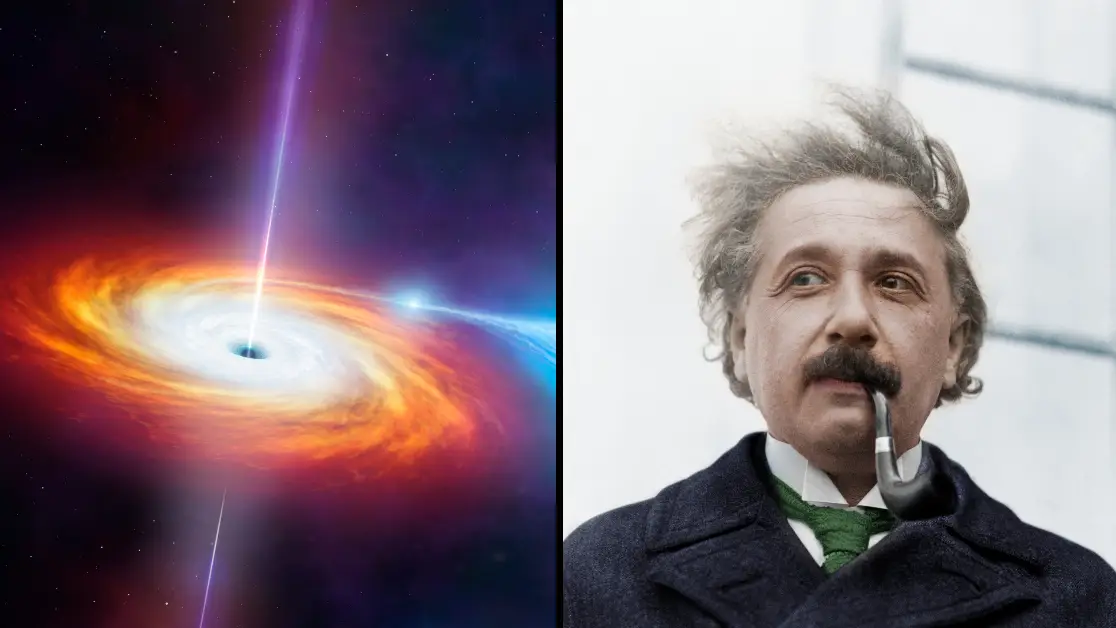

Now, their study has given the very first observational proof that a so-called 'plunging-region' exists around black holes. In normal speak, this is an area around black holes where matter stops circling the hole and instead falls straight in.

And not only this, the scientists found that this region has some of the most monstrous gravitational forces that have ever been found in the Milky Way galaxy.

Publishing the findings in Monthly Notices of the Astronomical Society, the work forms just one part of wide-ranging investigations into outstanding mysteries around black holes by astrophysicists at Oxford University Physics.

This study has focused on smaller black holes relatively close to Earth, using X-ray data gathered from NASA’s space-based Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) and Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) telescopes.

To follow the work up, the team are going to move on to recording the first videos of larger, more distant black holes as part of a European initiative.

Einstein’s theory states that when sufficiently close to a black hole, it is impossible for particles to safely follow circular orbits. Instead they rapidly 'plunge' toward the black hole at close to the speed of light.

It was this region that the researchers studied in depth for the first-time, using X-ray data to gain a better understanding of the force generated by black holes.

"This is the first look at how plasma, peeled from the outer edge of a star, undergoes its final fall into the centre of a black hole, a process happening in a system around ten thousand light years away," said Dr Andrew Mummery, of Oxford University Physics, who led the study.

"What is really exciting is that there are many black holes in the galaxy, and we now have a powerful new technique for using them to study the strongest known gravitational fields."

Astrophysicists have for some time been trying to understand what happens close to the black hole’s surface and do this by studying discs of material orbiting around them.

There is a final region of spacetime, known as the plunging region, where it is impossible to stop a final descent into the black hole and the surrounding fluid is effectively doomed.

Dr Mummery said: "Einstein’s theory predicted that this final plunge would exist, but this is the first time we have been able to demonstrate it happening.

"Think of it like a river turning into a waterfall – hitherto, we have been looking at the river. This is our first sight of the waterfall."

Topics: Science, Education, UK News, World News, Space