A Tennessee death row inmate has just two weeks to decide how he wants to be executed - and it's a choice not afforded to all prisoners.

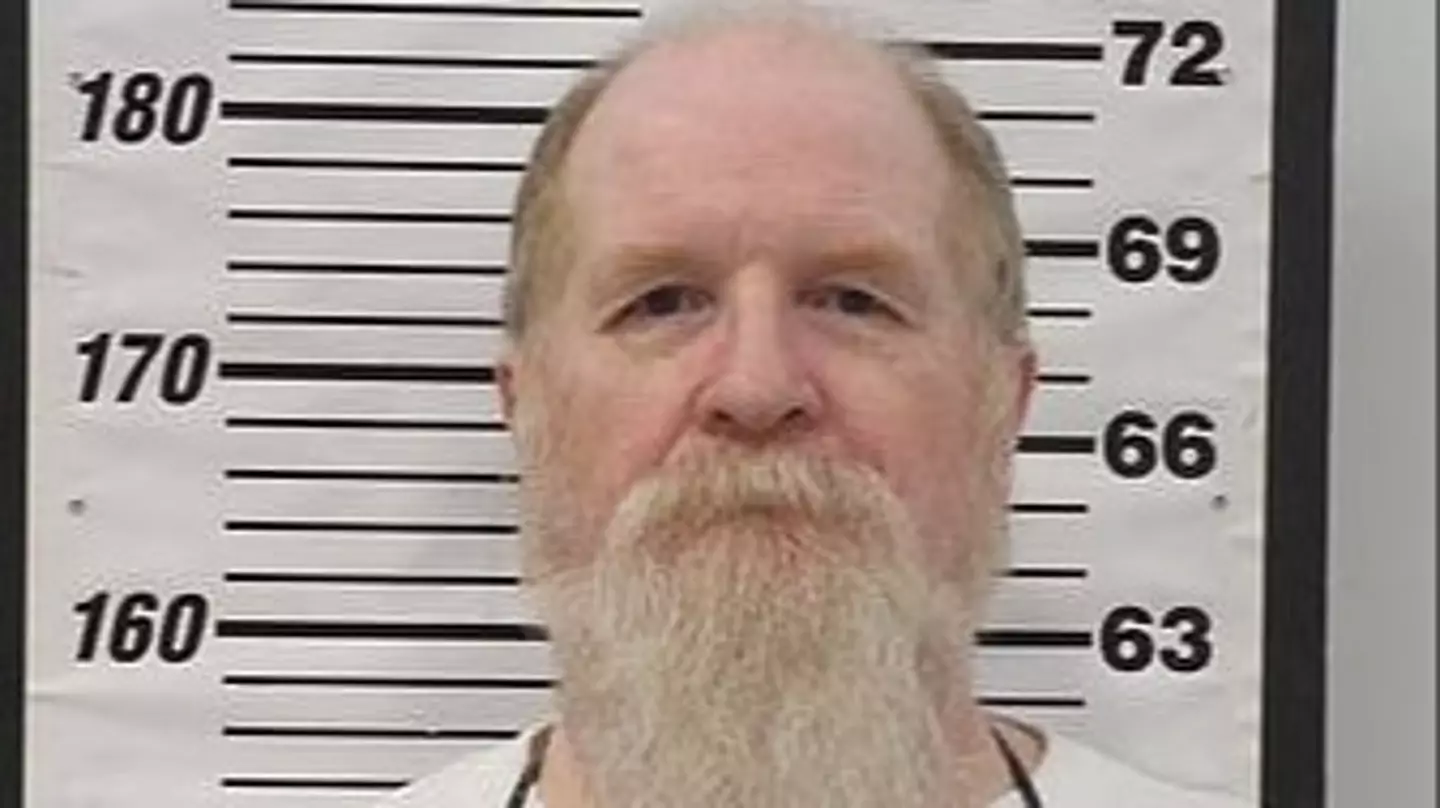

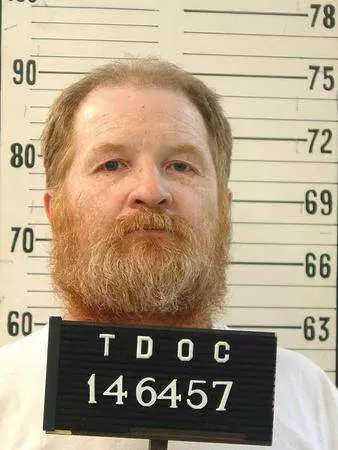

Harold Wayne Nichols was given the death sentence in 1990 after he was convicted of the rape and murder of a college student.

Court records state that two years prior, he broke into 21-year-old Karen Pulley's Chattanooga home and hit her on the head with a board at least four times, causing skull fractures and brain injuries.

Nichols was arrested on 5 January 1989 after police received information that he had committed several rapes in the East Ridge area.

Advert

He confessed to the rape and murder of Pulley in a videotaped statement and pleaded guilty to charges of felony murder, aggravated rape, and first-degree burglary for the offences against Pulley.

It now seems that Nichols has refused to choose between the electric chair and lethal injection for his execution on 11 December.

This means that the state will default to death by lethal injection, and the prisoner has just two weeks to overturn that decision.

He was set to be executed in 2020 and chose the electric chair, but his execution was postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Tennessee, inmates who have been convicted before January 1999 have the choice to opt for electrocution instead of lethal injection, the state’s standard method.

While a few states still allow the electric chair, it has been used only five times in the past decade in Tennessee.

Court documents state that Dr. Eric Engum, a clinical psychologist, testified that Nichols was of 'high average' intelligence and fairly articulate.

After he met with Nichols on multiple occasions, he diagnosed him with 'intermittent explosive disorder', which involves an 'irresistible drive to commit a violent, destructive act until the act is committed'.

"Dr. Engum testified that the condition may relate to organic factors or developmental factors such as a hostile environment, abuse, absence of love, and abandonment," documents state.

"In Nichols’ case, there was the presence of a harsh, hostile father and the abandonment of being placed in an orphanage after his mother’s death.

"Dr. Engum testified that Nichols was not a psychopath and was not always violent or evil; indeed, according to Dr. Engum, Nichols’ confessions reflected his 'good side taking responsibility for what [his] bad side did'."

The mental health expert concluded that Nichols 'would function well in an institutionalised setting but would repeat the destructive behaviour if released'.