A man who managed to survive a traumatic injury when an iron rod shot through his head before he vomited part of his brain out continues to baffle people today.

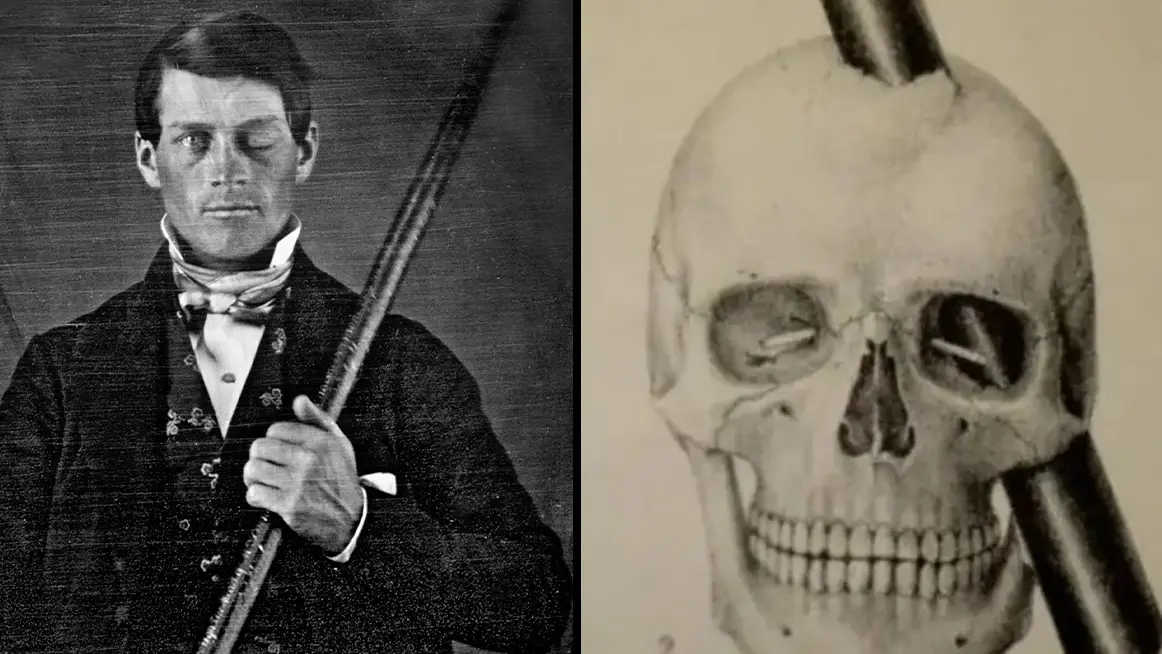

The strange case of Phineas Gage began in 1848 when physician and railroad executive Edward H. Williams rushed to the hotel in the town of Cavendish, Vermont to treat an injured man.

Gage worked as a blasting foreman, meaning he had to ensure rock didn’t block the advancing railway by filling holes with gunpowder and sand and igniting it to create powerful blasts. The full force of the explosion had to be directed at the rock, so Gage used a four-foot-long iron rod in the shape of a javelin to pack the contents of the hole down.

The 25-year-old and his team were working for the Rutland and Burlington Railroad on the afternoon of 13 September 1848 when a freak accident took place. Gage turned his head to chat to one of the men on his team when the iron rod came into contact with the rock and ignited the powder when it sparked.

Advert

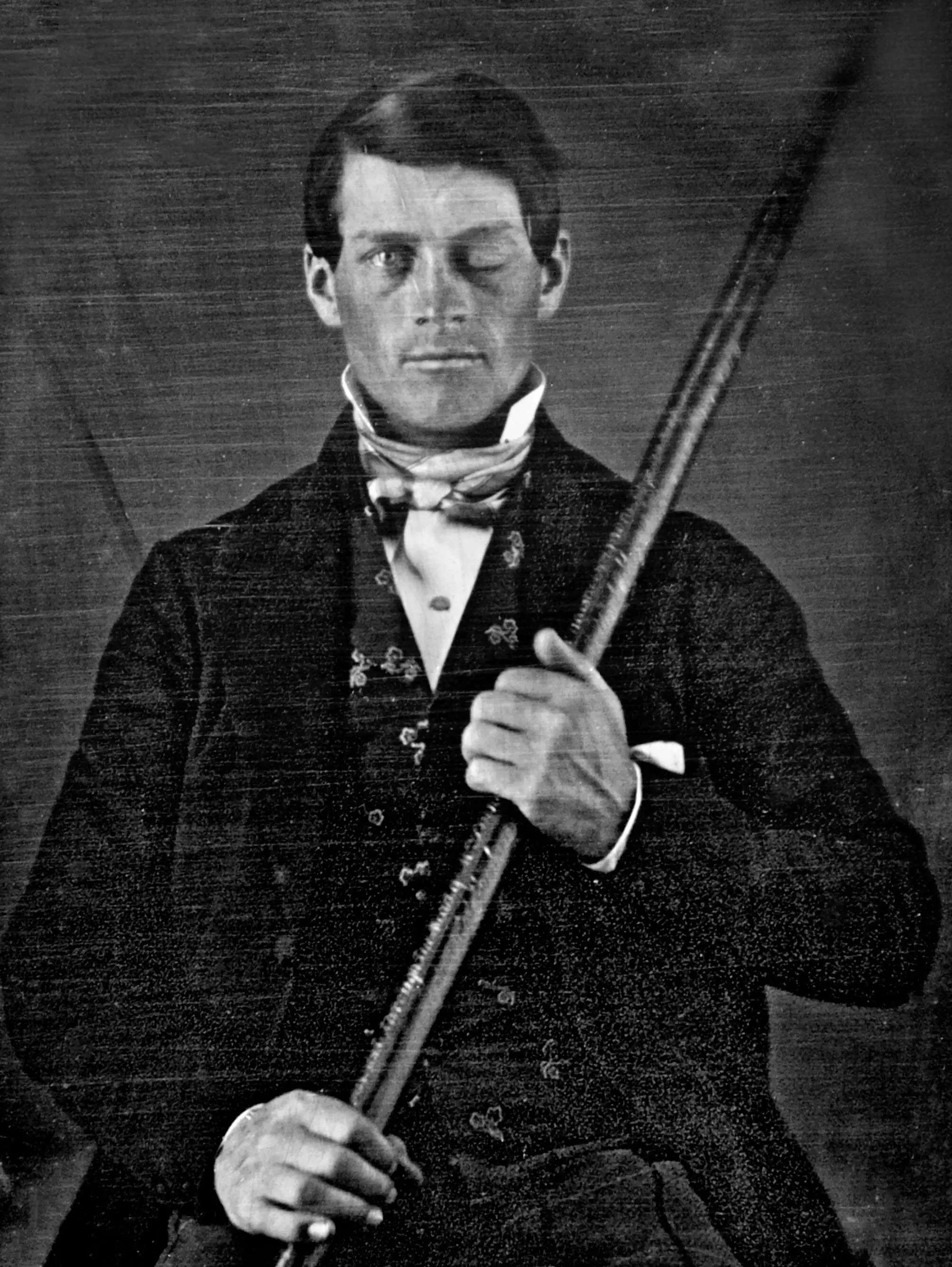

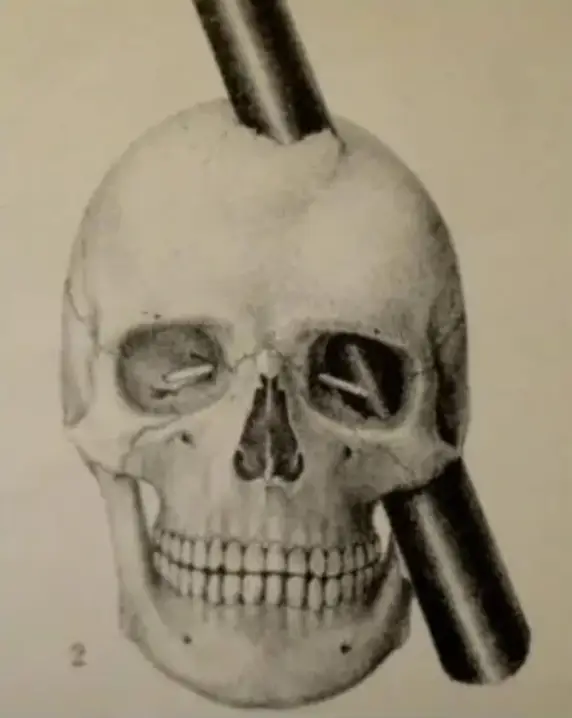

The force from the explosion that followed made the rod shoot out of the hole and directly through Gage’s left cheek and out of the top of his head, landing 80 feet away and unsurprisingly covered in blood and brain matter.

When the physician arrived to treat Gage, who had a big hole in his cheek and another in the top of his head, he was surprised to see that the man was alive and alert.

Not only was Gage still alive despite his injuries, he rose from his chair when Williams arrived before vomiting a large quantity of blood. Williams also noticed a piece of the man’s brain on the floor.

When the horrific accident occurred, Gage collapsed and convulsed on his back several times and then remained still. His team couldn’t believe that he was still alive and was able to walk without help to an oxcart that transported him into town.

Both Williams and John Harlow, the resident doctor in Cavendish, were sceptical about Gage’s survival story and we can’t blame them.

The doctors worked together to seal both holes in his head left by the rod and neither medical professional thought he’d survive his injuries. In the next few days, the physicians had to clean necrotic tissue and leaking pus from the wounds and 12 days after the traumatic event, Gage slipped into a coma. He once again defied the odds and 24 days after the accident he was back up walking and talking.

He lived for 12 years after the accident despite losing a significant portion of his left frontal lobe, but the lasting impact of the accident became clear. Gage wasn’t the same again after the accident and observers including Dr. Harlow, identified a personality change.

Before the rod went through his brain, he was a good-natured man but afterwards, he was very impatient, dismissive and had violent mood swings. He also developed epilepsy later in life and died aged 36 on 21 May 1860 of a seizure.

The Smithsonian Magazine has named Gage 'the most famous patient in the annals of neuroscience' because his injury was the first time a link was made between a brain injury and a change of personality.

The reason Gage survived the injury is because the fluid that would normally build up in the skull after a severe brain injury was able to drain away through his check, preventing inflammation, infection and haemorrhage and thus relieving pressure.

Gage’s mother gave permission for her son’s skull to be sent to Dr. Harlow for further study along with the rod. Both are now exhibited at the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School.