Sir Richard Henriques, the man who prosecuted the killers of James Bulger, as well as Dr Harold Shipman, has opened up on the cases that defined his distinguished career in a new book.

Whether in front of the bench or behind it, Henriques' career has seen him cast into the spotlight during the most significant legal proceedings the UK has witnessed over the past half century.

This includes the appeal of Barry George, the man who was acquitted of the murder of TV personality Jill Dando, the enquiry into Operation Midland, which saw high-profile British citizens accused of paedophilia and homicide, and the trial of the Chinese gangsters who were responsible for the deaths of 21 cockle pickers in Morecambe Bay.

However, two cases that feature defendants and victims at opposite ends of the spectrum of life have attracted public attention and enraptured a worldwide audience more than any others.

In the case of James Bulger's killers, the brutal and violent murder of a toddler by two boys, themselves not much older than their victim, left the world aghast at such cruelty from those so young.

Then, the trial of a respected and 'arrogant' doctor accused of murdering countless - and still disputed - numbers of his own patients left the UK reeling at the meticulous and calculated nature found in Shipman, who seemed to take pleasure in killing his elderly victims.

Both of these cases took place in the same courtroom - Preston Crown Court - and both cases saw Sir Richard Henriques tasked with bringing the killers to justice.

Now, in his book From Crime to Crime, Henriques describes the cases that have most deeply affected his remarkable career, and presents his treatise on the state of the UK's justice system in turbulent times.

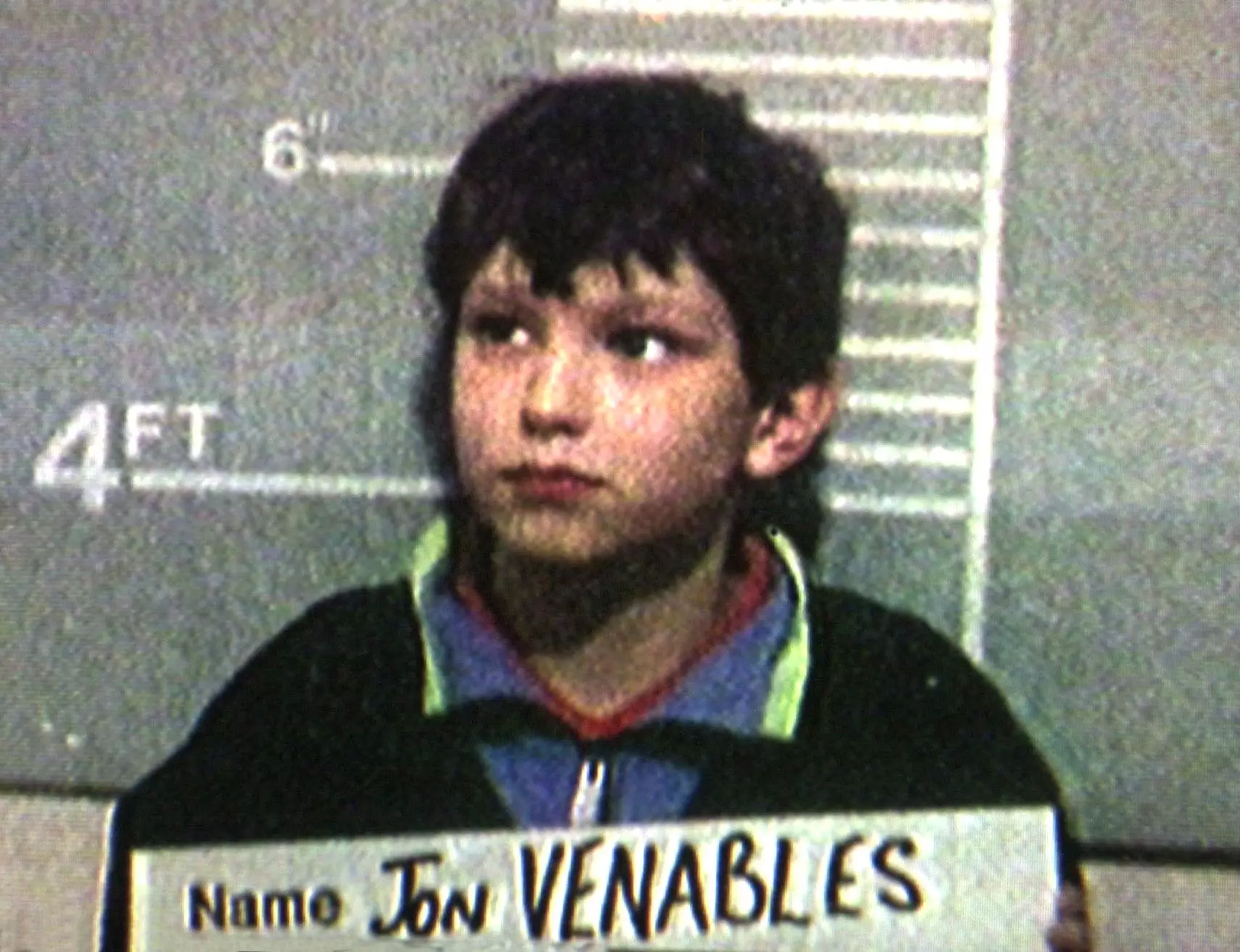

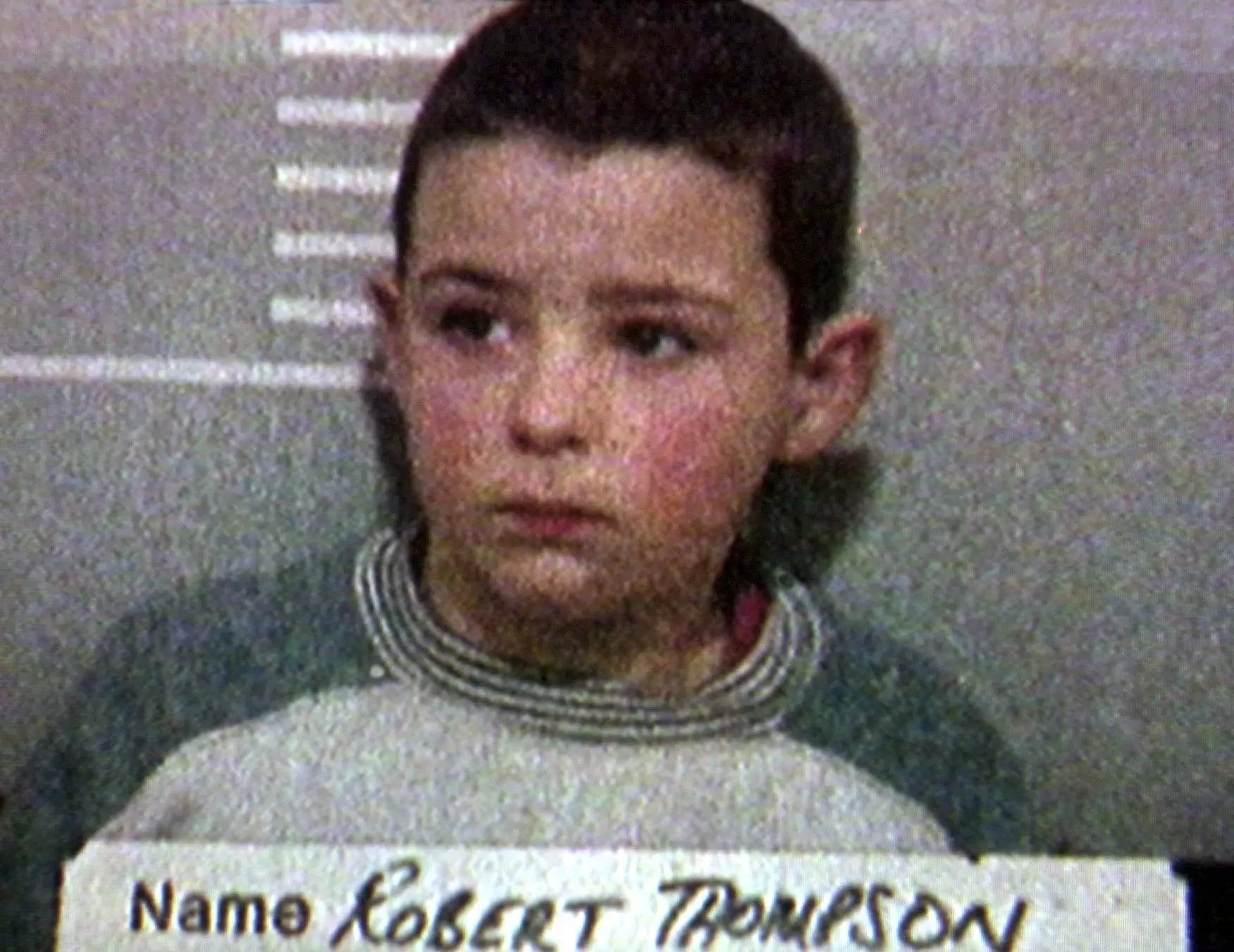

James Bulger was two years old when he was abducted, tortured, and killed by 10-year-old Jon Venables and Robert Thompson.

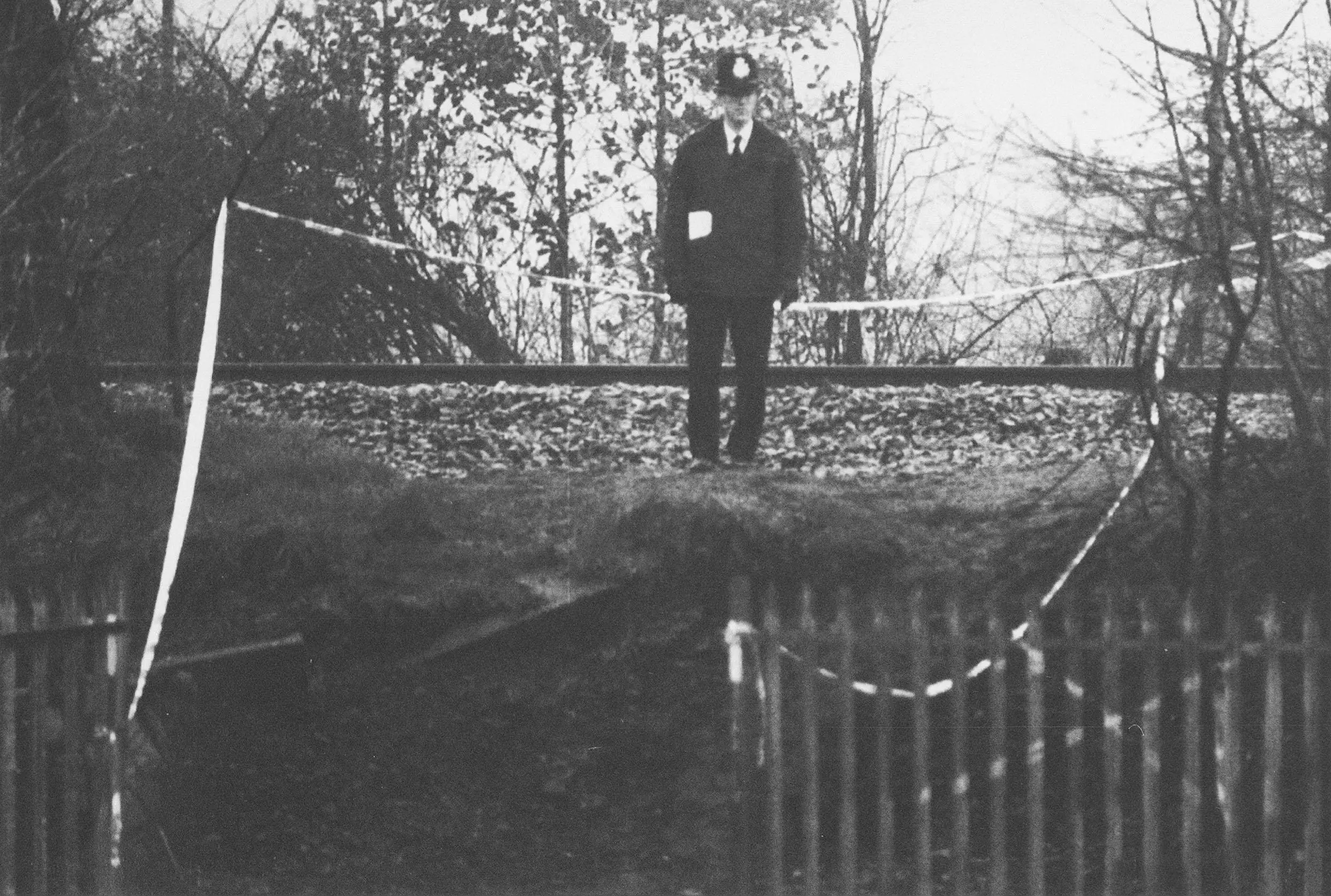

The two children abducted Bulger from his mother's side on February 12 1993, before his body was found several miles away on a railway track in Walton, Liverpool.

The boys had tortured James, abusing him in ways that doesn't bear fully repeating.

They remain the youngest convicted murderers in modern British history and the case - quite rightly - caused uproar in the local community and beyond.

It was Henriques' task to ensure justice for James' family and friends, which meant fighting the case for Venables and Thompson to be tried fully, and as adults.

He told LADbible: "I was perfectly satisfied that this was the appropriate way for them to be tried, subject only to some modifications in our trial process, such as the abandonment of wigs and gowns, and smaller courtrooms being used.

"The necessity for the two boys to be tried by jury, I think was perfectly proper."

"It was absolutely right - I think - that 12 jurors should decide, first of all whether the two boys both participated in the killing of James and secondly, that they should decide and be sure that both boys knew that what they were doing was seriously wrong.

"The idea that they could behave like this without it being a crime I regard as being at fanciful, indeed, bordering on the ridiculous.

"There was a great deal of evidence from school teachers, from psychologists, psychiatrists and educationists that children aged four or five know full well that you cannot stone, beat, and kick two and three-year-olds.

"So, the fact that 10-year-olds behaved like this certainly was a crime.

"I'm bound to say that had it not been treated as a crime, and had these boys not been required to stand trial before a jury, civil disorder would have would have erupted and a certain element of the Liverpool community would have taken the law into their own hands, so dreadful was this attack upon James."

In the chapter of the book concerned with Bulger's case, Henriques asserts that he believes his selection for the prosecution was - in part - because of the age of his son at the time.

His experience of having a child of similar age to the two defendants helped to ensure that the case could be handled in the fair-handed and delicate fashion that was required.

However, perhaps more unexpected might be the sympathy that seeing two boys of that age in the dock evoked in him.

He explained: "He [Henriques' son], and all his friends and contemporaries had taken an intense interest in the case.

"It was impossible for that age group not to do so because the case was on national television, local television, in great detail, daily.

"Of course, my own son had numerous questions to ask about it, and it was my responsibility as a father to answer those questions as well as I was able to.

"I do think that the whole of that generation almost certainly, throughout the country, learnt a great deal about caring for children and necessary ways of behaving towards them.

"I always thought that was a real possibility that public sympathy might at some stage swing towards them, for their predicament and finding themselves where they were, but it never did.

"It was a moving experience, seeing them in the dock, and even more moving listening to their interviews, particularly when Venables broke down whilst being interviewed by the police.

"Only a very hard hearted individual would not have had some sympathy for them, save and except of course, all those who knew baby James Bulger.

"It was impossible for them to feel any sympathy, and one understood exactly their thought processes."

In the end, the two boys were sentenced to a minimum of eight years detention, but have since been released and provided with new identities.

However, whilst Thompson appears to have settled into a normal existence - something he denied his young victim - Venables has been imprisoned on several other occasions since his release for crimes relating to indecent images of children.

Henriques continued: "I was sorry to see that Jon Venables had behaved in such a way that necessitated his recall to prison.

"Robert Thompson, on the other hand, appears to have lived a law abiding life. I'm a great believer in the ability of humans to reform and change their ways.

"Indeed, it's not too late for Venables to change his way of life and to be cured of what appears to be some form of addiction.

"But, the alternative was simply no action being taken.

"I've been assured by those who have been responsible for his treatment and for looking after him - members of the probation service in particular - that very intense methods have been used in attempts to turn both law abiding citizens, and I do hope that in due course both will do this."

Years after the conclusion of the Bulger case, Henriques was again called to Preston Crown Court, this time for a trial that started out - for all intents and purposes - as a forgery case.

Harold Shipman, a doctor in Hyde, was later found guilty of the murder of 15 patients, but this was just the tip of the iceberg.

Shipman is believed to be the most prolific serial killer in British history, and his total number of victims are thought by some to be in excess of 250.

His method of killing was to administer his own patients - predominantly elderly women - with a lethal dose of diamorphine, before falsifying documents and death certificates to appear as if the deceased were in poor health.

Chillingly, no genuine motive for his heinous acts has ever been properly determined.

Henriques explained: "I was told that I'd been instructed to prosecute a doctor who forged a will.

"When I inquired as to whether or not it was necessary for Queen's Counsel to prosecute a case of forgery, I was told that there was far more to it, and that it was a case they very much wanted me to prosecute.

"When I first met the police officers in the case, I was then told that they believed that they were dealing with a doctor who was a serial killer.

"Within two or three weeks, I was told that the numbers may be up to 100. So, then I realised that this was the biggest serial killer in [British] history."

In his preparations for the case - it would prove, crucially - he studied the case of Dr John Bodkin Adams, a doctor who had 163 patients that died in a coma, and 132 patients who had bequeathed money or items to Adams in their will.

He was acquitted in 1957, specifically because the judge ruled that 'the act of murder' had 'to be proved by expert evidence'.

Fortunately, expert medical evidence had come a long way by 1998.

"The elephant in the room was John Bodkin Adams. In Bodkin Adams' case there was a very clear motive - he was the beneficiary of under the will of almost all those whom he [allegedly] murdered.

"The Bodkin Adams case very much concentrated the minds of all of us who prosecuted. Quite why Bodkin Adams was acquitted is - to my mind - beyond comprehension.

"There are those who believe in his innocence. He was acquitted, and one has to accordingly concede that there must have been some doubt about his guilt, but there were 163 suspicious deaths in his case.

"Of course, science has progressed a great deal since then, and it was the scientific evidence that, in essence, proved guilt in Shipman's case."

Despite the overwhelming evidence in favour of the prosecution, there were moments at which is was conceivable that Shipman could be acquitted.

Toxicology evidence served by the defence showed that the embalming process, as well as medicines containing codeine could have skewed the concentration of the drugs in the victims.

Additional evidence showed that the drug pholcodine could convert to morphine in the stomach.

Henriques recalled: "Given a very short period of time, the prosecution had to gather together evidence to rebut the evidence that we had been served by the defence.

"So, until that vast amount of evidence had been very firmly dealt with, it looked as if there was a distinct possibility at least that we may not prove the case."

Of the defendant himself, a well-respected doctor who had turned to killing, it seemed so strange that an otherwise upstanding member of society - a doctor renowned for his bedside manner and regular home visits - could have resorted to such barbarism.

"We didn't see the best of him at the Crown Court. He was on the back foot, very defensive, arrogant, supercilious. He regarded himself as an equal of all the consultants that gave evidence.

"It's a great shame of course, because - had he had he not killed patients - it was absolutely plain he was an outstandingly good GP."

One thing that goes under-represented in cases such as these two, is the immersive nature of the job that counsel is asked to perform.

Whilst they are not directly related to the victim, and necessarily detached from the crimes themselves, it would not be human to be unaffected by poring over the details of cases such as these.

It is the case of James Bulger that left the deepest mark on Henriques, who has probably prosecuted more serious and violent crimes than anyone alive in the UK at the minute.

"The crime that affected me the most was the murder of James Bulger, there's no doubt about that.

"I was a comparatively junior Queen's Counsel at the time, and I think having conducted that case, and having seen the profile of that case - a huge, crowded courtroom with television cameras everywhere outside the court - by [the Shipman case] I was used to that."

"The sheer horror of the killing, the knowledge that two 10-year-olds could behave in the way that they behaved, when I had a son of similar age living in the same household with his friends visiting our home on a very, very regular basis.

"Looking at them playing football or going swimming and just recounting how Venables and Thompson had behaved is something that lived with me for some time."

The question that eludes both the public and those involved in the justice system remains - what makes people turn to such actions? How can two 10-year-olds become intent on murder, or a general practitioner turn to killing his patients?

Despite his experience, Henriques doesn't have the answer either.

"That's the question. What was it that made Venables and Thompson behave in the way that they did? What was it that made Shipman behave in the way that he did?

"That's a question that I think will probably never be answered.

"[In Shipman's case] They just enjoy doing it may be the best answer. If you do something over 400 times, it's difficult to think that he didn't enjoy it."

"There's no single answer. Every killing is case specific, as lawyers call it.

"You've got to look at each individual case.

"The first case in From Crime to Crime is Mrs. Merrifield. She was a housekeeper to a wealthy and elderly spinster, and she poisoned her with rat poison.

"In that case, it was greed, sometimes it's simply bad temper, sometimes it's sheer evil.

"It's a question that arises in every single murder case, and is a problem facing every judge.

"In sentencing, it's vital that a judge gives his views on a case so that the parole board, in due course, can consider it, and a lot of thought goes into that.

"A judge is helped by reports from psychiatrists and probation officers and the like into determining why on earth did he or she do that?

"There are such a variety of different reasons, but overall it's remarkable how murder cases rise and fall dependent upon the good health of the community as a whole."

In the case of the community as a whole, the judiciary and legal system of the UK faces an unprecedented challenge at the minute, and one that Henriques discusses at length in the final chapter of his book.

In that passage, he outlines a ten-fold way to improve the current justice system, whilst addressing long-standing problems that he believe have proven to be obstacles over his career.

He concluded: "The single most worrying feature at the moment is a huge backlog of criminal trials that are waiting to be heard, and the terrible length of wait for both victims and defendants - particularly defendants who are in custody - waiting to be dealt with who have no idea at all when they will be dealt with.

"The delay is getting longer and longer, and so long as social distancing is necessary it is just not going to be possible for the courts to get rid of this backlog.

"I'm - for my part - extremely concerned about this, and the only way I believe that it can be done is, for a limited period of time, for judges alone to try criminal cases.

"It's absolutely plain that some extreme measures are necessary to deal with this huge backlog of cases.

"Before Covid-19, the average waiting time in some courts was over 500 days, up from 391 in 2010.

"Now, that's far, far too long.

"My own view - back in the days when I was presiding judge of a circuit - was that we took every possible step to make sure that all criminal trials were heard within 12 months.

"When it reaches almost two years before a trial, people cannot remember where they were at a particular time.

"They cannot identify people, detail goes, memories fade.

"But - worst of all - victims in rape cases should be able to get it all over with, without having to relive the shocking event over two years after it took place.

"That's something they shouldn't be called upon to do, and because there is such a huge backlog at the moment, only seven percent of all crimes are being prosecuted.

"Without a jury, things can proceed at a much greater pace.

"Trials around the world take place by judge alone, but I'm a great believer in the jury system.

"[Juries should return] as soon as Covid-19 is dealt with, we have an effective vaccine, or indeed we get rid of this backlog, but something must be done to reduce this huge backlog of cases and that's my biggest concern at the moment."

Sir Richard Henriques' book From Crime to Crime: Harold Shipman to Operation Midland - 17 Cases that Shocked the World has been published by Hodder and Stoughton and is available to buy now.

Featured Image Credit: PATopics: UK News, lad files, Interesting, crime