A perfectly preserved dinosaur tail enveloped in amber has been found in Myanmar, Southeast Asia.

Now for those of us that are fans of Jurassic Park, we'll know that it was from preserved bones in amber that they managed to make the dinosaurs and an Attenborough was in Jurassic Park so we can get excited that this may actually be turning into a reality.

Well, perhaps not, but it's still an amazing discovery for the different reasons.

The specimen, thought to be from a juvenile coelursaurus, was found by Lida Xing, from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, at an amber market in Myitkina, Myanmar (what are the chances?) and is aged 99-million years, putting your favourite Scotch to shame. The jeweller selling it assumed it was some kind of plant matter but it later transpired to be the tail of a feathered dinosaur.

An artist's impression of a coelursaurus. Credit: Cheung Chang-Tat

Lida, through a lot of digging, managed to find the miner in question, too.

The co-author of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada with Xing, Dr Ryan McKeller, told the BBC: "This is the first time we've found dinosaur material preserved in amber."

"We can be sure of the source because the vertebrae are not fused into a rod or pygostyle as in modern birds and their closest relatives," he explained.

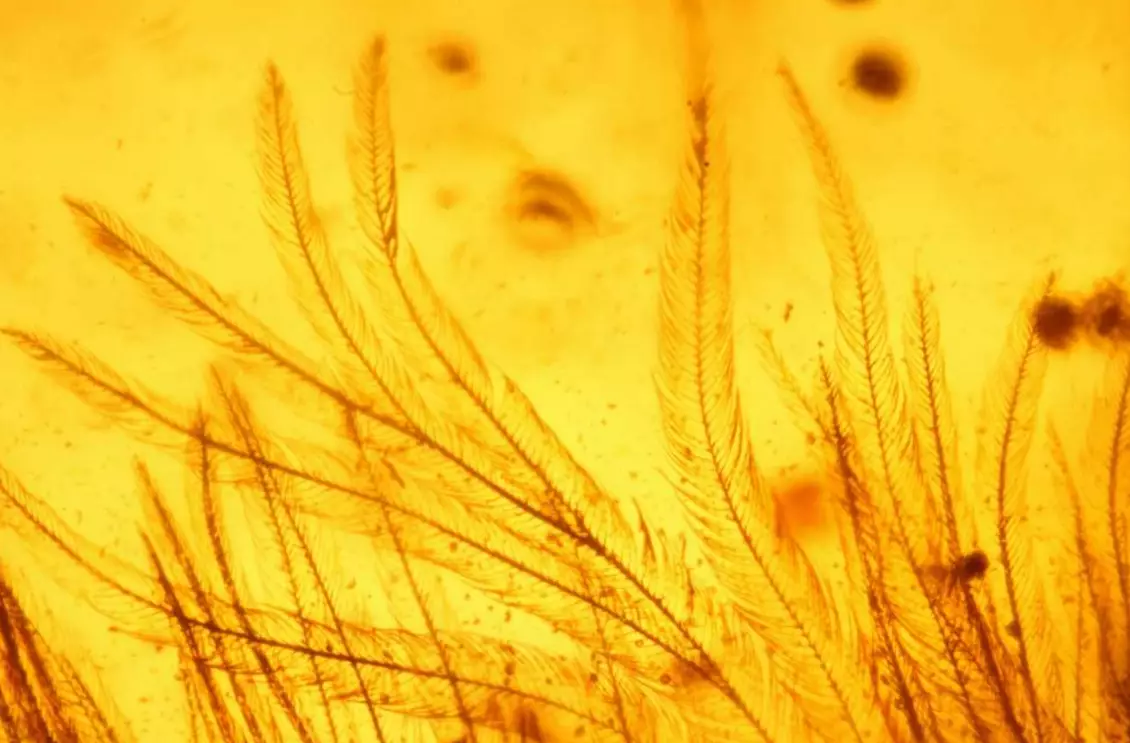

"Instead, the tail is long and flexible, with keels of feathers running down each side."

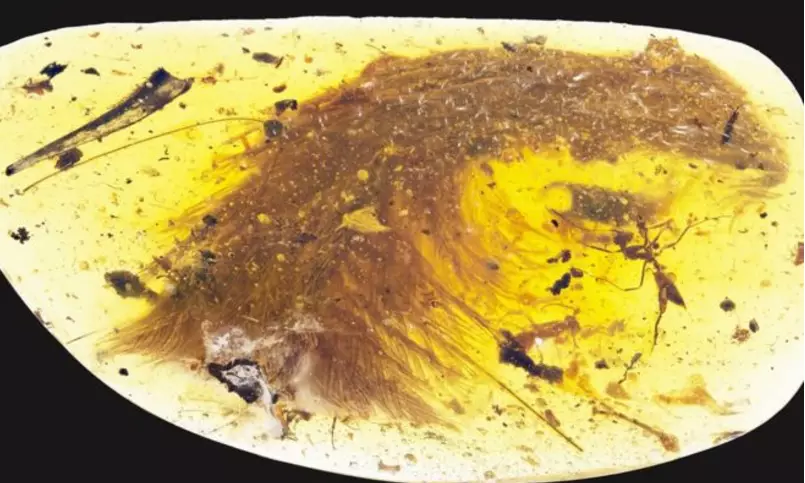

The piece of amber zoomed in. Credit Current Biology

Advert

Professor Mike Benton, from the University of Bristol, added:

"It's amazing to see all the details of a dinosaur tail - the bones, flesh, skin, and feathers - and to imagine how this little fellow got his tail caught in the resin, and then presumably died because he could not wrestle free."

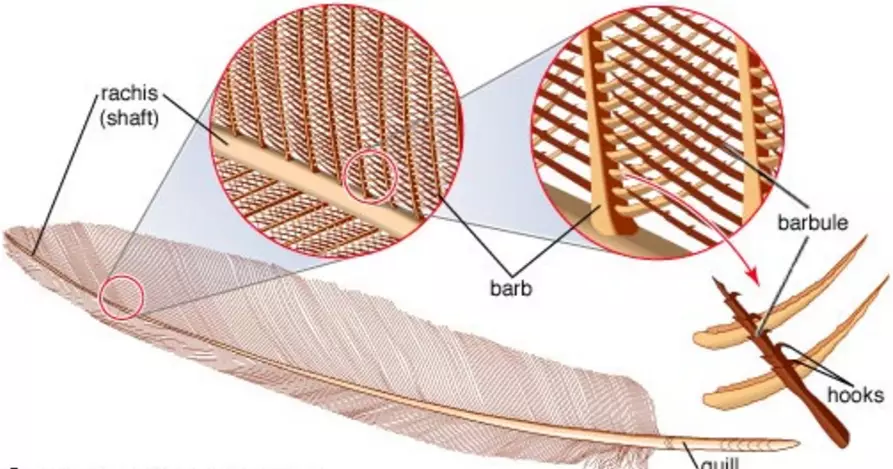

But what can we learn from it? Well the feathers do not have a well-developed central shaft, known as a rachis, like modern birds do. This suggests that barbs and barbules were made before the rachis formed and I'm not quite sure what I just wrote. Basically, it shows the evolution of feathers. This image illustrates the different components that comprise a modern-day feather.

Credit: Encyclopedia Brittanica

Advert

They are also hopeful that there's more out there in Myanmar, but worry that people purchasing the pieces mean they will be 'lost to science': "There have been other, anecdotal reports of similar specimens coming from the region. But if they disappear into private collections, then they're lost to science," said McKellar.

Main image credit: Current Biology

Featured Image Credit: