Nearly 40 years since the worst nuclear disaster in history, the Chernobyl exclusion zone remains off-limits to people.

In that time, just a few select people have been able to explore the area, which spans 19 miles around the worst reactive remains of reactor four, where the explosion took place.

The exclusion zone, or 'zone of alienation', was established to protect people from the long-term health complications associated with radiation poisoning, with the majority of deaths caused by radioactive iodine in the first few days and weeks, and the leading long-term cause being cancer.

One person to enter the zone was microbiologist Nelli Zhdanova, who led a team from the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences on a field survey mission in 1997, to find out what life could be found in the shelter where the destroyed reactor still lies.

Advert

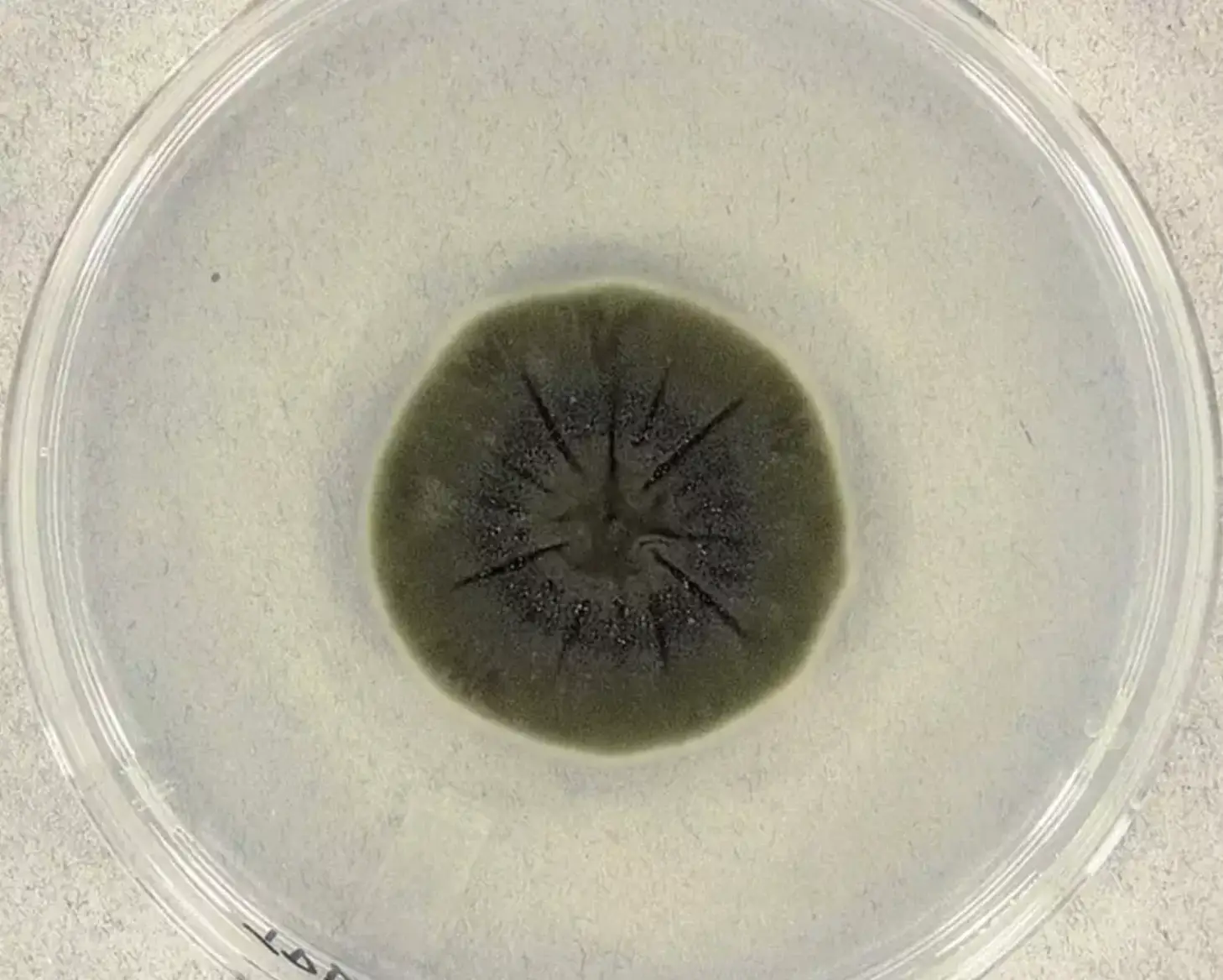

The team very quickly learned they were not alone, and found 37 different species of fungi, including black mould, which was previously believed to be detrimental to life.

However, the most bizarre aspect of Zhdanova's discovery was the fact that the mould, which had completely taken over the area, was growing towards the radioactive particles in that area, even reaching the original source of the radiation.

The team's research revealed that the fungal hyphae of the black mould appeared to be attracted to the ionising radiation, which would usually cause harmful mutations, killing organisms and destroying cells, but not in this case.

In the last two decades, Zhdanova has worked on pioneering research on what she calls 'radiotropic fungi', not only discovering what could potentially be a new foundation of life, but also providing hope that radioactive sites like Ukraine's Chernobyl and Fukushima in Japan, may one day be cleaned up.

Her findings could also help protect astronauts from harmful radiation as they travel up into space, BBC Future reports.

A complex study found that the radiotropic fungi, officially named Cladosporium sphaerospermum, could actually eat radiation, much like the way plants take sunlight to fuel their metabolic process in what's known as photosynthesis. This process is aptly called radiosynthesis and it's made possible thanks to the pigment in our skin and eyes, melanin.

The Cladosporium sphaerospermum has a dark shell made of layers of melanin and this takes the energy from the radiation and uses it to grow the fungus.

Scientists are still discovering exactly what these findings mean in terms of how they can be used in real life situations, but it certainly opens up a whole new world of possibilities.